The use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is already firmly embedded across a wide swathe of domains in the world of sailing – and it’s growing

The use of AI in sailing is distinctly different to the tools based on large language models such as ChatGTP and DeepSeek that became available in the last three years and garner a disproportionate number of headlines.

Other forms of AI have existed for many decades. Machine learning, and neural networks trained on transaction data, for example, have been used by major banks since the mid 1990s. They significantly improved detection of credit card fraud and anomalies in real time. But there’s been a rapid acceleration of AI’s abilities in the so-called deep-learning era post-2012.

Today AI is used across a wide swathe of applications in the boating world, encompassing safety systems, weather forecasting and routing, naval architecture, performance analysis, coaching and broadcasting. It’s also increasingly used in the domain of autonomous craft and we can expect to see it implemented to improve watchkeeping on the bridge of ships.

“AI at sea doesn’t need to be perfect – it just needs to be better than us at certain things,” says Yarden Gross, CEO and co-founder of ORCA AI, which supplies systems to shipping companies including MSC and Maran Tankers. “Let’s face a hard truth: the status quo is unsafe,” he adds. “Fatigued crews, complex navigation environments and over-reliance on human lookouts combined with ageing fleets operating with outdated technology – this is not a system worth defending.”

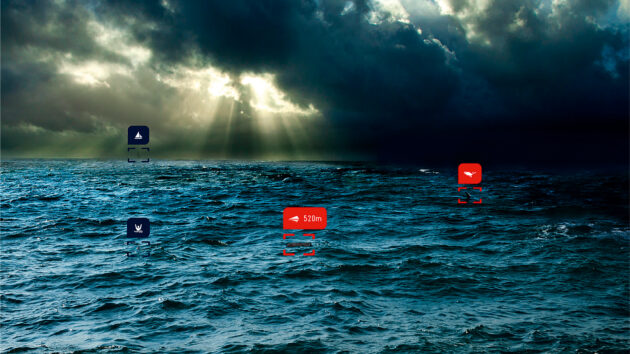

Demonstration of a Sea.ai warning of a floating container

Just be better

Instead, he says new technologies don’t need to achieve a fictional benchmark of flawless performance to be useful – they only need to outperform human crews in specific scenarios. “We’ve already reached the point where AI-enhanced watchkeeping is demonstrably safer and more reliable than a distracted, sleep-deprived officer of the watch, or in extreme weather and low visibility conditions,” he adds.

Gross proposes a hybrid intelligence with human and AI systems working together, each doing what they do best. “The phased approach – where ships dynamically shift between different levels of autonomy based on context – is the real revolution, and it’s happening already,” he adds.

“Ships today are gathering data, learning from every near-miss and self-improving at fleet scale. They are improving with every single voyage, feeding real-time operational data back into smarter algorithms.”

Article continues below…

Autonomous boats: The rise of self-sailing vessels

‘Vessel not under command’ looks set to take on a new meaning, with the race to develop a new generation…

Everything you need to know about high performance autopilots

It’s 0230 in the morning and we’re sailing close-hauled mid-Channel with the breeze gusting to 30 knots. In the strongest…

A new vision

Staying with the theme of safety, 65% of the competitors in the last Vendée Globe used Sea.ai systems to help identify small floating obstructions that had potential to cause significant damage. This system, originally named OSCAR, is mounted at the masthead and fuses a colour camera with two thermal night vision units.

The onboard AI then constantly scans the image streams looking for any unexpected deviation on the surface of the ocean. If it spots differences in temperature or pixel patterns, it flags and classifies objects, whether these are people in the water, whales, semi-submerged containers or other boats – and alerts the skipper in real time.

Demand for this technology is such that the company has grown from a start-up to 70 staff across three sites in only a few years.

Data from competitors in the 2020/21 Vendée Globe formed a big part of the input initially used to train the system, but that required a lot of human effort, so new data acquisition is now based on more specific learning points. Some of these, like a man overboard, are set up with the specific aim of training the system, while others are tagged by users at sea.

Sea.ai detects a shipping container and displays it on a Raymarine MFD

“Each software update is getting better with new data,” Sea.ai’s Solenn Gouerou tells me. She says new instances of raw data, for instance from a man overboard or encounter with sea ice, are constantly being fed back to the firm’s site in Brittany.

The confirmed detection is then sent to a team who annotates each contact in a way that can be understood by the neural network, for instance by marking a square in the sea with a caption saying there’s a person overboard in that area. The network is therefore constantly learning, with benefits rolled out to users via updates.

Weather gAIns

Weather forecasting and routing are also areas in which AI is increasingly playing an important role. Numerical weather prediction, which forms the basis of all of today’s weather forecasting, requires a huge amount of computing power and typically uses some of the planet’s most powerful supercomputers.

Yet AI has potential to improve forecasts and also reduce the amount of computing power needed. ECMWF launched its Artificial Intelligence Forecasting System (AIFS) earlier this year, running alongside its traditional physics-based IFS model. AIFS outputs are similar in many respects, and in some cases, such as tropical cyclone tracking, can be more accurate, while using a whopping 1,000 times less energy.

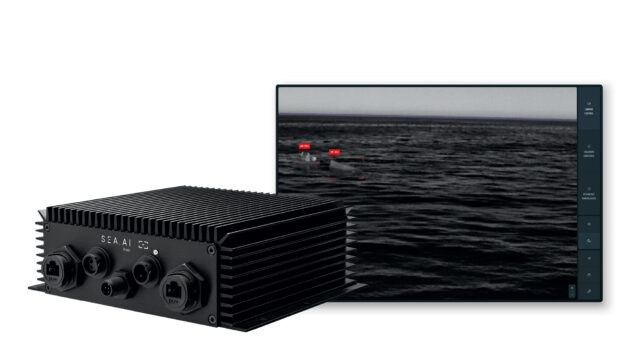

The family of Sea.ai cameras

This represents such a dramatic shift in processing requirements that low resolution global AIFS weather models can be run on high-end gaming laptops. Marine weather guru Christian Dumard’s start-up Marine Weather Intelligence aims to use AI to optimise routing, both for sailors and to help decarbonise shipping, and has clients including the Vendée Globe and The Ocean Race.

He says they use a lot of AI to analyse which weather models are best in different circumstances. That will vary, for instance, depending on the distance of a race or voyage. Satellites measure wave heights very accurately, so Dumard also uses AI to find the bias in wave models. “The wave predictions are quite good for the first two or three days,” he told an audience at last year’s Yacht Racing Forum, “but then the biases build, depending on the time of year and many other factors.”

He says AI is very good at unravelling complex problems such as this, “but the human brain is not so good at handling all the elements and AI is doing much better work.” AI-assisted forecasts are also starting to be fed into long-term routing decisions in ocean races.

Given the exponential growth predicted for wind-assisted shipping, driven by a reduction of long-term costs, there’s a huge amount of research and funding going into this sphere, which in the longer term will also benefit more ordinary sailors.

A unit mounted on the masthead of an Amel 50

Piloting

Ocean currents are notoriously difficult to predict in high resolution, yet their many eddies can have significant impacts on both sea state and passage time. Paris-based start-up Amphitrite has devised a way to use AI to measure currents using high-resolution satellite photos.

In an independent study, a ship travelling at 16 knots between Tunis and Tangier was shown to save 4% of fuel costs and arrive an hour earlier when using Amphitrite’s data for routing. To keep a boat on course and ‘learn’ the sea state, autopilots have always used PID (proportional, integral, derivative) control systems that were originally developed in the 1920s.

Some pilots even adjust these parameters in real time using heuristics such as measuring how frequently large heading errors occur, or how fast the heading changes. This can, for instance, trigger an automatic shift between calm, moderate, or rough tuning profiles, but it does so using predetermined criteria and not as part of an automated learning process.

As a result, many autopilots struggle in a big quartering sea, or when a short-handed sailing raceboat is fully powered up on a reach in gusty conditions.

By contrast, when AI becomes involved, the system itself either learns patterns or may use trained models to classify different sea states or predict optimal control parameters. Madintec’s MadBrain, for example, adapts its steering response over time, learning how the particular boat responds to waves, gusts and wind shifts.

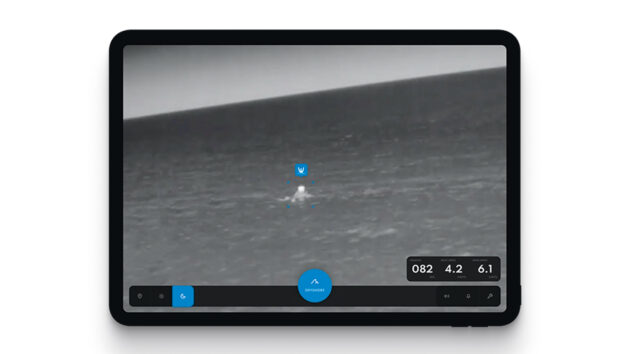

Thermal camera view of an MOB at night seen on an iPad

It’s a hugely powerful system used extensively in IMOCAs, Ultim trimarans and even foiling Mini Globe 650s. It’s also now becoming adopted more widely, including for very fast performance cruisers and in short-handed IRC offshore racing – the first four 33ft Pogo RCs, for instance, are all equipped with Madintec pilots.

Faster yachts and sailors

It’s perhaps no surprise that AI is used extensively in the America’s Cup, as it is in Formula 1. QuantumBlack (the AI arm of global consultancy firm McKinsey), for instance, created an AI virtual sailor for Emirates Team New Zealand ahead of the last Cup.

This was trained on a simulator by a top-level Olympic sailing sailor in a process that took only one or two weeks. After that, it could evaluate an astounding 50 different foil designs, across a range of wind and sea states, and on a weekly basis. What once took months of human-led testing on the water can therefore now be done in a few days – an important factor in reducing the development costs of America’s Cup boats.

Onboard display and the Sea.ai ‘brain’

QuantumBlack also built physics-based AI models replicating fluid dynamics and other complex systems, allowing rapid and efficient exploration of design options and iterations that are far more cost-effective than conventional CFD (computational fluid dynamics). AI is well embedded in the broadcasting of sailing events to the public.

SailGP and the America’s Cup, for instance, use machine learning to classify the boats, marks of the course, spectator craft, and shoreline to help create live 3D graphic overlays. “Once we know the relative position of the helicopter in space, that allows us to be able to draw the graphics in three dimensions on the video,” says Joseph Ozanne, simulator and AI team leader for Alinghi Red Bull Racing.

Helping hand

Assisted docking systems such as Raymarine’s DockSense and Volvo Penta’s Assisted Docking also use AI for improving the control logic or machine learning-based object recognition that helps the system positively identify items such as pontoons and other vessels in a marina environment. Thanks to AI, it’s now easier than ever to get accessible knowledge out of data through automated analysis.

We’re even heading in a direction where, within two or three years, it’s likely to be possible to run your own very high-resolution weather models using consumer-grade software and a laptop.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.