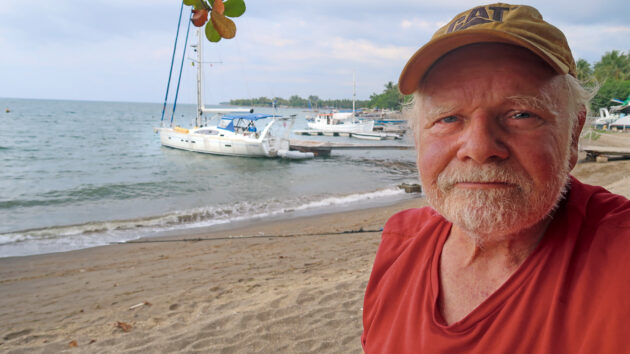

Trading his aircraft for a 41ft yacht, 74-year-old Harry Anderson completed a challenging, multi-year voyage, including a stop in Antarctica

When ocean sailors are quizzed about their voyages, the most common question they are asked is: “Were you ever scared?” Harry Anderson insists he was not, but when he had to crawl forward and fix a broken **genoa** furling line alone in the Drake Passage amid storm force winds and seas, he realised he was chillingly vulnerable.

“Going south had been easy, but going north was a disaster,” he recalls. “There was a lot of fog. A huge storm came between Cape Horn and 60°S so I put in a bit of westing and heaved to, to wait out the storm. But I lost out the westing and I just had to start to cross.

“It was the most challenging time, trying to fix the broken line and furl the sail back in with frigid water crashing over me, up at the bow. I felt I earned my chops. But I said to myself, this is what this is about. This is reality.”

Harry Anderson has been a man on a mission for 15 years. In 2011 he flew his light aircraft solo around the world eastabout and in 2019 carried out the same feat westabout.

In between, he made a lone flight to Antarctica and back, becoming only one of five aviators ever to do so, as well as a daring and lengthy transpolar flight over the North Pole. Satisfied with the record flights he’d done, he began to consider an around the world sailing voyage, and the possibility of setting a new record as the first person to both fly alone and to sail alone to all seven continents.

Anderson with his plane. Photo: courtesy Harry Anderson

He accomplished this on 29 January 2025, sailing his 41ft Allures 40.9 Phywave back to Fort Lauderdale two years and five months after leaving Norfolk, Virginia.

He’d spent 350 days at sea and logged over 38,000 nautical miles, crossing the Atlantic to the Azores, Portugal, Morocco and south to Brazil, round Cape Horn to Antarctica, across the Pacific to Australia and via the Indian Ocean to South Africa, before crossing the Atlantic for the third time to return home to the US.

Anderson, now 74, lives on Bainbridge Island, near Seattle. An electrical engineer and entrepreneur, he built up a company designing wireless communication networks, sold it – then bought it back four years later and transformed it once again.

As a young man, he studied for a PhD in England, hitchhiked across Africa and has worked on four continents; his outlook is decidedly global. He has always had a taste for travel and for adventure, and the time and means to enjoy his freedom.

Photo: courtesy Harry Anderson

A Family Dream

The seeds of his aviation and sailing ambitions are there in his family background. His father had been a radioman in the Navy, flying on patrol bombers out of RAF Dunkeswell in Devon to search for German submarines. His parents were both keen sailors and for a time lived aboard a yacht.

It had been their dream to sail from San Diego to Baja, and perhaps far beyond, but his mother fell ill, then died, and his father moved ashore. When his father later died, he left his sextant to Harry.

Anderson was 48 when he got his private pilot’s licence. In 2011 he made his first round the world flight in a Lancair Columbia 300, a small, single-engined plane he’d chosen because the back seat could be removed to fit in extra fuel tanks.

In 2018 he flew over the North Pole, from Resolute Bay in Canada to Longyearbyen, Norway, then in 2019 flew alone around the world for a second time, through Russia, Japan, China and Kazakhstan. Sailing had been an early interest, but never anywhere near the scale of his airborne adventures.

After moving to Puget Sound Anderson bought a Bavaria 37. “I sailed it for 12 years up the Inside Passage to Alaska, and learned about different things,” he says.

Flying over Svalbard having crossed the North Pole. Photo: courtesy Harry Anderson

“But I sold it in 2018 and thought my sailing days were done. It wasn’t until 2020 that I resurrected the idea of sailing round the world. Like everyone else [in the pandemic], I was sitting around at home twiddling my thumbs, and changed my mind.”

Anderson decided he needed an aluminium yacht to sail to Antarctica and ordered the Allures. At 40ft it is small these days for such a trip, but he knew the loads would be manageable.

“It was similar in size to the Bavaria 37 so I knew I could handle it alone,” he explains. He had the boat shipped from Southampton to Baltimore, US, and the sails, watermaker and generator fitted there.

He chose a Schaefer furling boom and electric winches to make sail handling easier solo.

King George Island, Antarctica. Photo: courtesy Harry Anderson

Ticking Countries Off

Anderson’s round the world voyage route did not include a sightseeing itinerary. “I planned the route to land on all seven continents most efficiently, with the shortest way, and I typically planned a week in each place.

“I was not on a cruise around the world, not there for tourism; I was truly on a mission. Part of that was that I had already been to many of these places, and they were not a mystery to me,” he reflects. The first night at sea after leaving Norfolk, Virginia, for the Azores was also the first time he’d sailed overnight on his own, and it was a turning point.

“I went to bed at 2200. I didn’t set up some bizarre sleep schedule. I thought ‘I can’t do that’, so I went to my bunk in the aft cabin, and slept and I let the boat sail on its own, no one steering or keeping watch.

It convinced me I could do that – you have to look to the electronics to be your crew. “Not many days later, I found that when I was sleeping I’d become very sensitive to the motion of the boat and I could quickly detect the wind increasing from the [sound of the] wind generator overhead.”

From the Azores he and Phywave sailed to Portugal, then to Morocco and Lanzarote, from where Anderson struck out for Brazil, crossing the Atlantic for the second time in three months.

He kept his pace steady, with a simple sailplan of poled out genoa, staysail and mainsail, using a boom brake to reduce the energy when gybing. His logs from those passages are matter-of-fact, finding little to remark on other than the emptiness of the ocean, occasional pods of dolphins and schools of flying fish.

Pago Pago. Photo: courtesy Harry Anderson

Burned Out

By the end of 2022, Anderson was working south from Mar del Plata in Argentina, trying to dodge tidal currents and headwinds on his way to Patagonia.

In early 2023 he left Puerto Williams in the Beagle Channel and turned south across the Drake Passage, making landfall in fog at Deception Island and anchoring in the dark bay of its submerged volcanic caldera.

A week later he was making his way back in fierce weather, anxious to press on into the Pacific. Looking back, he remarks: “I regret not venturing further on, but I was evaluating the risk and it was riskier to extend into more difficult waters.

You have to set shore lines and one of my issues was I was unable to do that solo – when you go ashore there’s no one on board to keep position.”

Reaching Puerto Williams again he felt he badly needed a rest. “I was pretty burned out from sailing and living on the boat. The preceding seven months had been intense sailing, covering more than 12,000 miles. I was due for a break.”

On the beach at Deception Island, Antarctica. Photo: courtesy Harry Anderson

The next stage beyond Chile would be a 2,200-mile voyage to Nuku Hiva in the Marquesas. Instead Anderson flew home for six weeks, and got a delivery crew to take Phywave onwards to Puerto Montt, in southern Chile.

It would mean missing out five degrees of longitude, so the voyage would fall short of a full circumnavigation. “But,” he says, “my real objective was sailing solo to seven continents.”

From French Polynesia across the Pacific, the tone of Anderson’s logs changed. With his increasing ease on Phywave, and the sporadic winds of an El Niño year, a philosophical mood crept into his writings.

“I’m sailing west across the Pacific into a setting sun, a common sailor fantasy now real, though I still see the clouds above me as a pilot would, not a sailor,” he reflected. “The days [flow] together with no distinguishing features, the tradewind direction and speed finally fairly steady.

The sky suddenly clouds over then just as quickly brightens to brilliant blue, seemingly at random, followed by nights lit up with a moon waxing full. It’s the upper half of a world that has the hypnotic, twisting rhythm of the waves beneath. And me in between.”

A toast with whiskey while crossing the equator southbound. Photo: courtesy Harry Anderson

Long Haul Home

The slog from La Réunion to Richard’s Bay in South Africa, one of the most notoriously hard passages, was one of Anderson’s biggest tests. Struggling against the strong Agulhas Current and low pressures that funnel up the African coast, he remembers “raising my arms to the sky and saying ‘Why are you doing this to me?’

“I felt like I was being put upon. I had put up with a lot and I deserved a break. At the time, it felt so unrelenting.”

But after a rest in South Africa he was ready for the last long haul home to the US, stopping in Walvis Bay, Namibia, St Helena and finally Antigua for some ‘Dark ‘n’ Stormies’ – as well a complicated repair to an autopilot drive unit.

He arrived back in Fort Lauderdale on 29 January, 2025 to the fanfare of family and friends.

Lombok, Indonesia. Photo: courtesy Harry Anderson

An End In Itself

Today, Anderson is back on Bainbridge Island and Phywave is on the hard near Annapolis, the other side of the country. He’s contemplating his next adventure: sailing through the Northwest Passage.

He has already flown the route by plane, landing in Barrow, Alaska. “It would be the most interesting way home,” he muses. He would again make that voyage solo. “I guess it’s what I have gotten used to, being alone,” he says.

“People ask me this about flying as well and I say I’m like a road cop that nobody wants to ride with. It would be weird and uncomfortable even bringing friends who are sailors.”

He always viewed a plane or a yacht as vehicles for an adventure and a goal, but the long voyages in Phywave took on a meaning he did not entirely anticipate. “When I am out there in the ocean that’s the part I enjoy the most.

I don’t look at ocean crossings as something to be done to get it over with. It’s a destination in itself. “In retrospect, I think I really should have savoured some of those moments more.

Sailing in rough seas. Photo: courtesy Harry Anderson

I felt that as I left St Helena – in some ways the most remote place I’ve ever been. As it receded in the distance, and it was clear this voyage was coming to an end, I said to myself: I have to savour being out here, being able to see horizon to horizon with no other boats and nothing on the radio.”

Anderson’s accounts of his voyage (on phywave.com), can be sparse and startlingly matter of fact – he was certainly not pitching for film rights. But the voyage became something more than just a companion record to his aviation feats.

His penultimate entry, alongside a big photo of his father’s sextant in its wooden case, reads: “I’ve carried my Dad’s sextant with me everywhere I’ve sailed for the past two-and-a-half years, across the world’s oceans, to seven continents, several countries and dozens of harbours and anchorages around the globe,” he writes.

“In this small way [my parents] were along with me, sailing the world as they once dreamed of doing. I think they’d have liked that.”

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.